You have already read here how this, my first album of the year, was chosen simply because it was the only album I owned at that time. So I suppose the first question must be – with the benefit of hindsight , would I have picked a different one instead of With the Beatles ? The answer probably more reflects the times than any other records specifically.

You have already read here how this, my first album of the year, was chosen simply because it was the only album I owned at that time. So I suppose the first question must be – with the benefit of hindsight , would I have picked a different one instead of With the Beatles ? The answer probably more reflects the times than any other records specifically.

In 1963, we were on the cusp of a social revolution that is now considered by some as being the source of all of this Nation’s ills, particularly when viewed through the wrong end of a telescope by people who were not even born when it happened! The truth is that it was the year when the world of baby-boomer working-class teenagers, such as myself, finally began to emerge from the gloom of the post-war years we had experienced from birth. Up until then, everything felt grey – from the soot-covered stone of the buildings to the raincoats that all the grown-ups wore as they walked through streets where, twenty-years after the event, the jagged outlines of bombed-out buildings were still silhouetted against the smoggy skies.

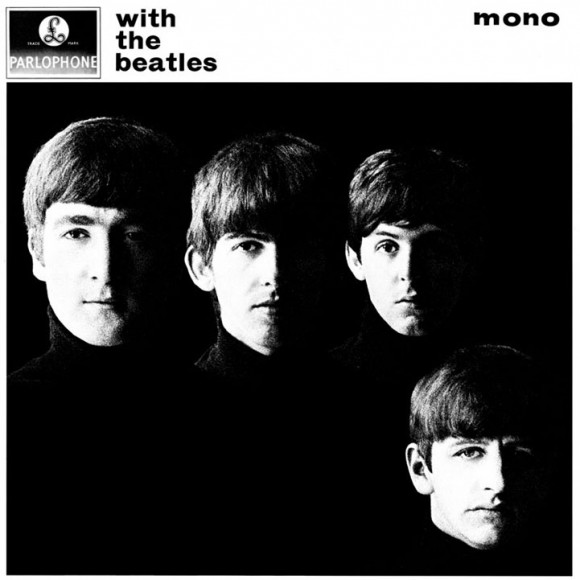

Even this iconic album sleeve is monochrome and, in my case, it held a monaural recording because I couldn’t afford the extra five shillings and sixpence for the stereo version; even if I could have, our mono record player would have played just one channel. And yet, despite the lack of colour, the promise is there in that photo of four lads with strange haircuts wearing black polonecks, a photo that caused our PE teacher to observe that ‘only poofs wear polonecks’. Following the inevitable protestations from the class, he added a postscript: ‘you’re right, they can’t be – poofs visit the barber regularly’. Such bigotry merely shielded his generation from what they already knew: that image said one thing quite clearly – this record is different.

It had to be, because up to the middle of 1963 the album charts reflected what our parents were buying for themselves – film soundtracks and artists considered as trendy but ‘safe’; even Elvis had swapped his jeans for army fatigues. The first Beatles album, Please Please Me, was also safe, containing both sides of their first two singles along with covers of songs by acceptable modern songwriters, the likes of Goffin & King, Bacharach & David; even the sleeve just showed four cheeky-chappies looking down from the EMI balcony during a break on the day it was all recorded. On the 11th May 1963, just a week after their third single From Me to You gave the group its first number one, Please Please Me also went to number one in the album chart. It stayed there for more than six months until December 7th when it was replaced by this album.

As the sleeve photo had hinted, this album was also different musically. Fourteen brand new tracks, none of which were ever released as singles, the first of several statements that it made. Eight were written by the group themselves, with the first five tracks on side one all self-penned, reinforcing that this record was what the band themselves wanted to do, and it was for the fans. The opener, It Won’t be Long, like many early John Lennon songs, sets the tone by going straight into the chorus. It is followed by another Lennon song, All I’ve Got to Do, which features some unusual (for the time) bass licks from Paul McCartney. Track three All my Loving is a typical McCartney pop track and probably received as much airtime back then as a single would have. It is followed by George Harrison’s Don’t Bother Me before going back to a joint Lennon/McCartney number in Little Child.

Next comes the only cover that could be considered ‘establishment’ coming from the Broadway Musical ‘The Music Man’. Till there was You was the only Broadway song the band ever recorded, and had been used as part of their audition for Decca Records almost two years earlier, from which they famously failed to pick-up a recording deal; I like to think it was included here just to cock a snook in that direction.

The final track on side one is the first of four Detroit covers, Please Mr Postman. Originally released in 1961 by The Marvelettes, it was the first Motown single to top the American charts. What has to be borne in mind is that what, in these PC-times, we now call MOBO was anything but mainstream in 1963, and although we Brits like to see ourselves as always having been multi-cultural, the music charts over here featured almost-exclusively white artists at that time. So including just one black artist’s soul track on any album in 1963 would have been a risk; four was a statement.

Those of us who were lucky-enough to have a local record shop that picked-up occasional shipments of American singles with labels like Chess and Stax, already knew a little of Blues and Soul, but both were still essentially underground sounds. They never featured on the BBC, and rarely on Radio Luxembourg; it wasn’t until the pirates like Radio London and Caroline emerged the following year that a wider audience was introduced to them in this country. Even the first Motown number one over here, Baby Love by the Supremes, was not available in the UK on Tamla Motown, but released on a label named ‘Stateside’, owned by EMI, who were very specific in what they allowed through.

Side two of this album opened-up with another cover, this time of Chuck Berry’s Roll over Beethoven. The track had been part of the band’s live act almost from when they started, but otherwise Chuck Berry’s music was rarely heard over here during the early-sixties, mainly because of his reputation. In fact, he was still in prison when the Beatles recorded this track for the album, another edgy aspect that is probably lost on today’s audience, but said a lot about what this record was about.

The rest of side two featured Lennon/McCartney tracks alternating with Detroit ones. Hold me Tight was a McCartney composition and is followed by Smokey Robinson’s You Really Got a Hold on Me with John Lennon on vocals. The next Lennon/McCartney track I Wanna Be Your Man had distinct Chess influences, and was released by the Rolling Stones as their second single the week before this album came out. Even though it only reached the middle of the singles chart, I have to say that Mick Jagger’s vocals made theirs a far edgier version than this one, which features Ringo up front.

The next track, Devil in Her Heart was written by an obscure Detroit artist, Richard Drapkin. It was recorded by the Donays on the Correct-Tone label, but wasn’t a hit. Correct-Tone, however, were a major competitor of Motown at that time, and were the label that started many Detroit artists on their careers, most notably Wilson Pickett and, for a few weeks, The Temptations.

Another John Lennon song, Not a Second Time, came just before the final track gave the album a rousing finish. Money was co-written by Berry Gordy and, when originally recorded by Barrett Strong in 1959, had been the first hit for Gordy’s original Tamla label. It clearly shows the influence of Detroit and Chicago not only on this album, but on the early Beatles’ songwriting, particularly John Lennon’s. Listen closer to All I’ve Got to Do and Not a Second Time and you will recognise the early Smokey Robinson sound not far beneath the surface; you could also easily be forgiven for thinking I Wanna be Your Man had been written by Chuck Berry.

So there you have my answer: this album may not be an out-and-out classic, but it is a true milestone. It marks the point at which British popular music split away from the dead hand of Tin Pan Alley and Denmark Street and embraced other musical cultures. It was album of the year for 1963 because it gave us a message – that despite the world appearing to be monochrome, beneath the surface there lay all manner of colours waiting to burst forth.

If you want to download or stream this album, here are the links:

| Artist | Album | Download | Stream | |

| The Beatles | With the Beatles |

I have also compiled a playlist containing fifty of the best tracks from 1963. To stream the playlist on Spotify, click the logo below: