Looking back at my notes for this year, I was really surprised just how many albums I bought, especially in view of the general circumstances, of which more in a moment. Regardless, the choice of Attack of the Grey Lantern at the end of the year wasn’t difficult.

This was the year when, after 30 years in the industry, I finally became the owner of my own publications company. I had formed it about seven years earlier in partnership with a friend who had his own design consultancy, and originally grew it under that banner as a support to their design work. But within a couple of years it had grown sufficiently to need its own individual identity, and that was how we had traded for a further five years before it became obvious it had diversified so far from the original concept that the time had come to go our own ways.

Buy-outs are not simple, especially when the companies have shared premises and some staff for many years, so the year was consumed with physically moving the operation to another town, meetings with banks and lawyers to sort out all manner of issues, both anticipated and unexpected, and keeping Clients on-board by retaining services while we did all of that. But we got to Christmas with our staff happily ensconced in our new premises, and our independent workload increasing, although it would be another few weeks before the dotted line was actually signed.

Which is why I initially found it difficult to remember how I found the time to listen to and select over sixty albums, let alone go to the record shops to buy them – on-line sites like Amazon didn’t even exist in the UK until the following year, nor sold music at all until 1999. I also did a huge amount of travelling, not only by car in the UK but also to the ‘States where I had acquired a large client a couple of years earlier. Which, I then remembered, was where some of the purchases were made – anybody who has experienced the Aladdin’s cave of a US independent music shop will know what the first experience of the sheer range on offer felt like. And I had a good mate over there who knew where the best shops were.

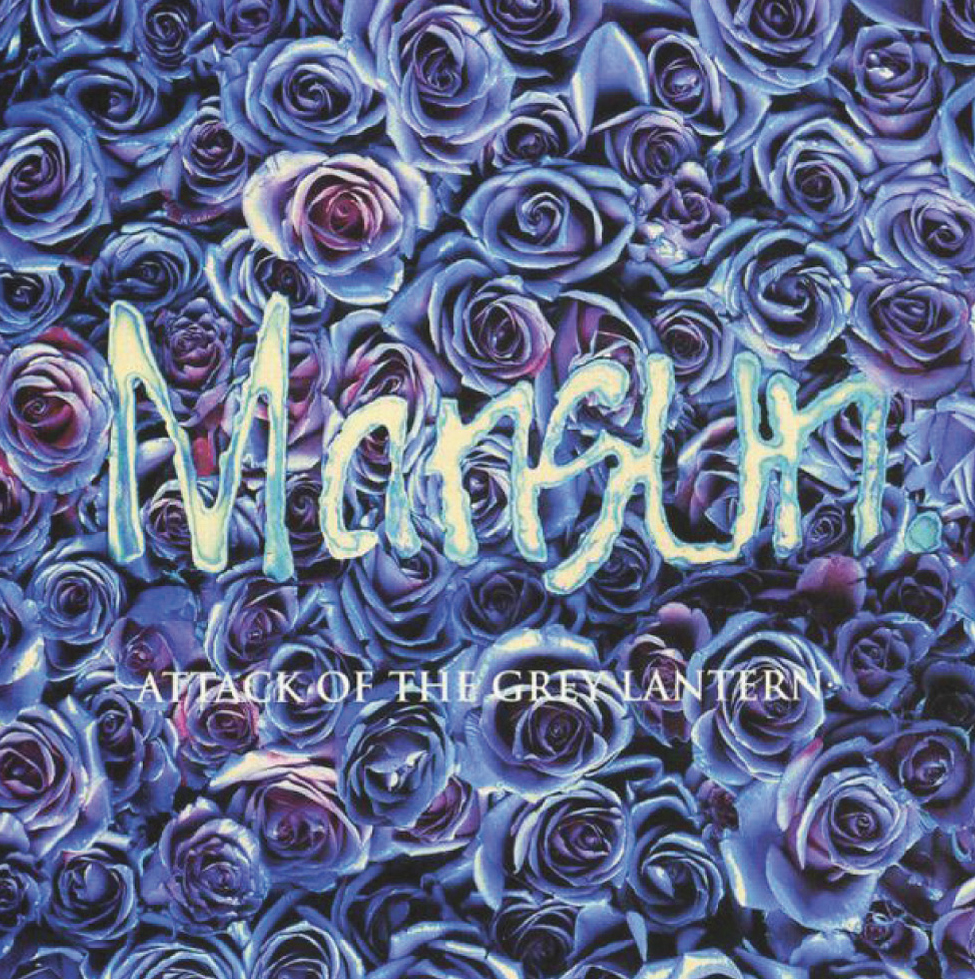

But it was on UK radio the previous year that I first heard Mansun, driving home late at night listening to John Peel to be exact – if I had a tenner for every time that happened, etc, etc….. Contemporaneously hearing numerous different tracks on the radio is always the sign of a good album, and I bought this one on that basis immediately it was issued. Regular readers will know how much I like a good concept album, and when I first listened to Attack of the Grey Lantern in its entirety, that is exactly the feel it had – although exactly what that concept may have been was never entirely clear at the time.

Some years later, during an interview, lead singer Paul Draper revealed that, apparently, the ‘Grey Lantern’ of the title was meant to be his superhero alter-ego sorting out a village full of immoral residents – yeah right. And that is where anyone coming to this album over twenty years later may be confused by a lot of the stuff written about it by newbie muso-journalists entranced by Draper’s exposé-style interviews that were more a part of relaunching a solo career that never really took off after the band folded. So, if you’re new to this album, I strongly recommend listening to it a few times and coming to your own view before indulging in the history.

Because musically, the album fulfils all the criteria for a classic – not a bad track anywhere, each sits perfectly in its own space between those on either side and the flow is perfect – on first listening you even left it running after the last track knowing the hidden track obviously had to be there. On release, it went straight to number one in the album chart, an early indicator of the emergence of alternative bands whose music was popularised by small gigs and word of mouth, rather than the tired old pop radio stations who never played them at peak times until they were blind-sided by their success.

The line-up for the album recordings was co-founder, songwriter and frontman Paul Draper, co-writer and lead guitar Dominic Chad, co-founder and bass Stove King plus Andie Rathbone, their third drummer, who arrived towards the end of the sessions and ended-up re-recording most of the percussion parts. The album was co-produced by Draper and Ian Caple, the latter also being a newcomer on the scene at the time. Possibly more importantly it was mixed by Spike Stent, who had been around for more than ten years working with the likes of Massive Attack and Depeche Mode, but whose profile was really raised by this project – just look him up to see what albums he has been involved with since that have earned him, among other things, five Grammys.

The album opens with a string intro that morphs effortlessly into an underlying guitar riff that wouldn’t be out of place in a spy movie theme. The Chad Who Loved Me then becomes somewhat of a time-shift mix between pure ancient prog and contemporary Britpop meaning, both then and now, there is plenty enough going on in these opening minutes that is different enough from the run of the mill to make you sit up and listen. As the opening track fades away into strange animal noises, in comes Mansun’s Only Love Song which, like a lot of this album, isn’t what the title might suggest as there is little romance here – unless you class narcicism in that category.

Track three, Taxlo$$, was a successful single that has probably become more infamous for the Roman Coppola video in which twenty-five-grandsworth of fivers were thrown off the bridge at Liverpool Street Station during rush hour with the ensuing filmed public scramble being the subject matter. Whether or not, as has been suggested, the track itself was actually influenced by The Beatles’ Taxman, there is no doubting it does have an underlying late-sixties psychedelic feel to it.

The next track You, Who Do you Hate? fades in under sounds of wartime London and is a bit sinister both in musical and lyrical construction, but a great track nevertheless until it fades out to the same background into Wide Open Space. That this track became a hit single is no great surprise, as it has a steady driving quality that builds through the chorus to a crescendo ending. If this had been conceived as a vinyl album, this would have been a great end to side one, as it finishes with a simple piano notation which, had it been followed by silence, would certainly have impelled you to turn it over.

I have always thought track Six, Stripper Vicar had something of a Tears for Fears feel to it. It was the band’s first top-twenty single some months before the album was released, but in the album context retains the sinister undertones and links to the next track, Disgusting, via a short ethereal sequence. The bright musical tone somewhat masks the dark lyrics of both of these two tracks, but the venom begins to show through in track nine, She Makes my Nose Bleed, which is followed by the somewhat plaintive pleas of Naked Twister.

The album begins to draw to a conclusion with track ten, Egg Shaped Fred, which has always felt to me more like a Beatles tribute, even down to the Lennonesque list of made-up names. The last track, Dark Mavis, is supposed to be the unfrocking – or should that be refrocking – of track six’s Stripper Vicar with all the finalé musical tricks and signatures of the ending of a tragic opera. And it works perfectly.

The final, and fashionably hidden, track An Open Letter to the Lyrical Trainspotter is, according to Paul Draper years later, a sort of musical epilogue providing a full revelation of the story in the album. I’ve never really bought-into that as, lyrically, the whole thing is very tongue-in-cheek. The impression I gained at the time it was released, and retain even after several critical relistenings whilst compiling this blog, feels more of a sideways swipe at religious hypocrisy; which is the question I would have asked him were I one of the young NME-style pups granted an interview a decade ago.

No, regardless of the post-historical narrative, for me the lyrics are not what Attack of the Grey Lantern is about; they are just a reason for enshrouding them in one of the most glorious musical envelopes of that era.

As well as this album, 1997 produced a fairly varied list from which to choose the final three: Blue Moon Swamp from John Fogerty, White on Blonde by Texas, Verve’s Urban Hymns, Abra Moore’s Strangest Places, Music for Pleasure by Monaco, my first tentative toe-dip into rap with Supa Dupa Fly by Missy Elliott, two albums by (at that time) teenage American guitar prodigies Trouble is… by Kenny Wayne Shepherd and Lie to Me by Jonny Lang, OK Computer by Radiohead, Paul Weller’s Heavy Soul and the debut eponymous album from Marcy Playground.

The top three at the time were Attack of the Grey Lantern, Urban Hymns and OK Computer. White on Blonde came close, but it ultimately lost out because the standard of the three standout tracks, Say What You Want, Halo and Black Eyed Boy were way above the rest. Although American-sourced albums featured heavily in the long list, only Strangest Places was ever in any serious contention and remains an album that is played quite often. As is the Monaco one, but mainly due to Peter Hook’s amazing basslines.

So now the 64 dollar question – would I choose any of the others over Mansun? The answer, once again, is no. I still play Attack of the Grey Lantern regularly, but the others rarely other than Strangest Places – I often wonder what happened to Abra Moore, as one of the tracks on that album, Four Leaf Clover, was Grammy-nominated, but afterwards she just disappeared. Radiohead ran Mansun close at the time, but I now prefer their 2016 album A Moon Shaped Pool and, although The Verve’s live Glastonbury appearance in 2008 was genuinely something-else, their albums just don’t live up to that any more.

If you want to download or stream any of the top three albums, or some of the others mentioned, here are the links:

I have also compiled a playlist containing fifty of the best tracks from 1997. To stream the playlist on Spotify, click the logo below: